(Bloomberg) — President Joe Biden’s $52 billion bid to transform the domestic chip industry — one of the most ambitious pieces of US industrial policy since World War II — is about to enter a pivotal stage: life under a new administration.

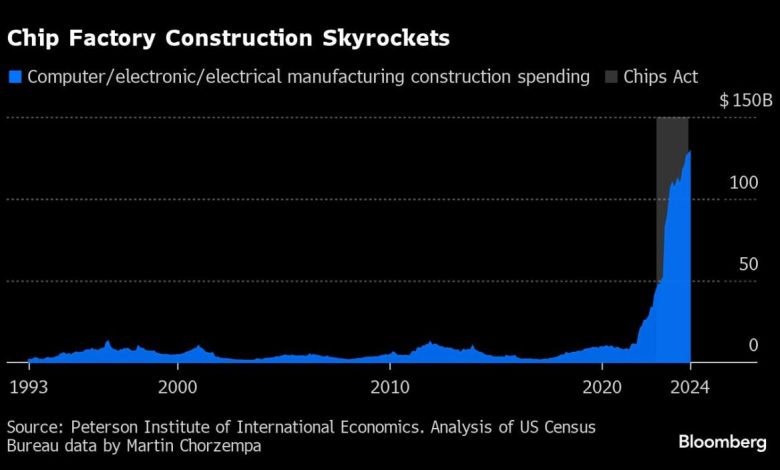

The Biden staffers overseeing implementation of the bipartisan 2022 Chips and Science Act are wrapping up work this week and preparing to hand over duties when Donald Trump takes office on Jan. 20. They had the task of allocating $39 billion in grant funding — along with loans and tax breaks — to usher in a chip-factory building boom. That’s on top of separate money for research and development and international semiconductor programs.

Most of the grant funding has been awarded, and the initiative has spurred more than $400 billion in planned company investments. But much of the job remains unfinished — and broader upheaval in the chip industry will only add to the challenges. Two of the program’s biggest participants, Intel Corp. and Samsung Electronics Co., are mired in slumps. And getting many of the new factories up and running will take years.

But the amount of activity that’s already underway constitutes an “inflection point” for the US semiconductor industry, the Commerce Department’s Mike Schmidt, who has led the Chips Act rollout for more than two years, said during a wide-ranging interview. It “puts us in a position to be hugely successful going forward.”

The goal is to reduce reliance on Asia for the tiny components that power everything from microwaves to missiles. If the planned projects work out, the country will boost manufacturing across the entire semiconductor supply chain and make around a fifth of the world’s advanced processors by the end of the decade — up from near-zero today.

So far, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. has been a highlight of the effort. After a rocky start that triggered a debate over whether the US can successfully execute industrial policy, the chipmaker now has Arizona facilities that outperform comparable factories back home. It recently began commercial production at its first Phoenix plant and plans to bring its most advanced technology to the US in the future, albeit only after it debuts in Taiwan.

But the two other key makers of leading-edge processors, Intel and Samsung, have both scaled back their manufacturing ambitions: Intel by postponing projects in other countries, and Samsung by reducing the size of its Texas investment. Intel also is seeking a chief executive officer after ousting Pat Gelsinger last year, and it’s unclear what strategy a new leader will pursue.

Schmidt acknowledged that some Chips Act participants may change their plans even after striking final deals with government officials. “The program will evolve with that,” he said.

Then there’s the question of what Trump will do. Before the election, he described the Chips Act as “so bad” and suggested tariffs would be a better solution. But Trump’s cabinet pick who would oversee the program, Howard Lutnick, has signaled that he’ll stay the course.

Lutnick told Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo in a recent meeting that he’s committed to the initiative, she said at a staff gathering last week, according to people who were present. A Commerce spokesperson declined to comment, and a representative of Trump’s transition team didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The law enjoys broad support on Capitol Hill, though Republicans have indicated that they want to repeal what they see as “social” provisions of the Chips Act. That could involve eliminating labor-friendly regulations or environmental requirements.

There is always the possibility that Trump’s team tries to reopen negotiations for binding deals. Vivek Ramaswamy, who will help lead an external government efficiency advisory body for the new administration, has pledged to review the spate of awards that Biden officials raced to finalize before leaving office.

The outgoing team says those agreements are ironclad. But throughout negotiations, some companies worried that certain contractual language leaves room for Trump officials to make adjustments, according to people familiar with the discussions. A particular concern: The deals allow a wide range of government remedies, including clawing back funds, if companies violate a variety of conditions. That could be triggered by things as minor as missing a paperwork deadline.

“We had to come up with a legal construct that both protected taxpayers — in a way that we thought was consistent with our programmatic objectives — while clearing the market and being commercially viable from the perspective of our applicants,” Schmidt said. “Ultimately, we got there. It was hugely challenging.”

All told, Biden’s team completed 20 deals and reached preliminary agreements for 14 others. Some of those awards include loans, though officials wound up using very little of their $75 billion lending capacity. For most companies, the biggest chunk of federal support will come from 25% tax credits.

But it’s “very, very clear that the grants have been the most impactful part of what we’re trying to do,” Schmidt said. Asked whether the US could have won the same company investments with much larger tax breaks — say, 50% — rather than this approach, Schmidt said that direct funding negotiations provided crucial “leverage to secure specific commitments.”

That included TSMC’s public pledge to build a third facility in Arizona, Schmidt said, as well as confidential agreements with Samsung and GlobalFoundries Inc. to produce specific older-generation chips that are important to national security.

“That kind of stuff doesn’t happen for the tax credits, right?” Schmidt said.

Asked whether tariffs could have lured chipmakers to American soil, as Trump suggested, Schmidt said that tactic has “a role to play in industrial strategy.” He pointed to a recent Biden administration trade probe that could lead to tariffs on less-advanced Chinese-made semiconductors. “But there’s no question,” Schmidt said, “that the incentives provided by the Chips Act were essential.”

Looking ahead, Intel is perhaps the biggest source of uncertainty. The Silicon Valley icon is due to get the largest Chips Act award, and it set out under Gelsinger to spend $100 billion on factories in four US states — including a flagship facility in Ohio.

But in the two years since Biden called the Ohio site a “field of dreams,” the company has lost Wall Street’s confidence, cut 15% of its workforce and delayed its factory timelines.

Intel remains committed to its US projects, company and government officials have said, even as it pulled back from other investments in Europe and Asia. Government money will only be disbursed as those plants hit construction and production milestones — and as Intel reaches specific technology goals.

But at a senior level, Biden officials recognize that Intel’s success could require more drastic steps. The chipmaker’s current leadership says it’s still an open question whether the company gets split up, which could have serious consequences for the manufacturing business, particularly if Intel chooses to sell any of its factories. (There are some ownership constraints built into Intel’s Chips Act award, which effectively gives the government a say in the company’s future.)

One idea that’s gotten some attention from senior government officials is a possible deal between Intel and GlobalFoundries, according to people familiar with the conversations. Some key officials think GlobalFoundries could be a compelling partner because it’s already a trusted Pentagon supplier, the people said, and Intel has a $3 billion agreement to make chips for the military.

GlobalFoundries is also the only other major chip foundry based in the US, so the result would be one American company that makes everything from routine semiconductors to cutting-edge processors. One potential hitch: Mubadala Investment Co., the investment arm of the Abu Dhabi government, owns about 80% of GlobalFoundries.

But while the idea has come up in multiple meetings between government and GlobalFoundries officials over the past several months, plans haven’t progressed much past a thought exercise, the people said. GlobalFoundries exited leading-edge production years ago because it couldn’t win enough orders to sustain high levels of investment, and it doesn’t have the money for an acquisition.

That’s not unlike the challenge currently facing Intel, and it’s one reason that the US needs investment from foreign firms to achieve its semiconductor goals.

Shares of GlobalFoundries gained as much as 8.7% to $44.50 on Friday after Bloomberg News reported on the discussions. Intel, lifted by earlier takeover speculation, rose 8.3% to $21.31 as of 1:08 p.m. in New York.

Representatives for Intel, GlobalFoundries and the Commerce Department declined to comment.

Asked about the risks of new Intel leadership changing its investment plans or splitting up the business, Schmidt said that his office has confidence in the company and wants to see it succeed — but the program also has spread out its bets.

“Intel’s an important part of the portfolio,” he said. “It’s one piece of the portfolio.”

–With assistance from Ian King.

(Updates with GlobalFoundries shares in ninth paragraph after third chart.)

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.